Reading this article requires some understanding of:

Linux distributions,Linux Desktop Environment,Package Manager

My first encounter with Linux was in high school, when there seemed to be a software that only had a Linux version, so I tried to install Arch by following online articles. I don’t remember the specific details anymore. For me at that time, a bunch of incomprehensible commands were quite a headache, and I was always afraid of breaking my computer.

During university, I used a dual-boot system for a while. In daily use, the Linux system was particularly prone to “breaking”, and the reasons were varied and bizarre. Looking at it layer by layer, hardware compatibility/kernel/drivers/system libraries/dependencies/desktop environment, etc., could all have bugs. These components are also somewhat disconnected from each other, so problems are common. Occasionally solving one or two problems gives a sense of accomplishment, but too many just feel purely troublesome.

There’s a specific example that made me want to laugh while also relating deeply: Linus Tech uninstalled his desktop environment while trying to install Steam.

In 2020, I accidentally came across Flatpak, and within a short time, I went all-in with Flatpak for my daily software. Later, I also maintained several software packages I wanted to use on Flathub. In terms of daily experience, I no longer have to worry about software not working after updates, don’t need to manually manage software updates, no longer worry about unruly closed-source software, and no longer worry that system updates will break my main software.

After using Flatpak, I decided to make Linux Desktop my primary system.

What Problems Does Flatpak Solve

First and foremost, decoupling from the system. This specifically solves the problem that Linus Tech encountered above. Actually, something similar has existed on servers for quite a while, namely containers, that is, the Docker ecosystem. Friends who have been exposed to Linux distributions should be particularly familiar with package management, along with concepts like dependencies, repositories, source code, packages, FHS, etc., though we won’t discuss how this system specifically works here.

Let’s look at how Linus Tech accidentally damaged his desktop environment. The installation command was sudo apt-get install steam, followed by a large output, which included a warning WARNING: The following essential packages will be removed, and this included pop-desktop, which ultimately led to the desktop environment being uninstalled. Some people would point out that this is because Linus Tech was unfamiliar, or that the installation guide and critical package protection weren’t handled well, or that it’s a problem with package management, or that using Linux as a desktop system is just stupid and deserved.

Looking beyond the phenomenon to the key issue, first, installing user software requires sudo. There’s a good analogy, which is UAC in Windows systems. Friends who frequently use Windows systems must have heard the term reinstalling the system, right? So why do you need to reinstall your system from time to time? A major factor is that most of the software you use daily requests UAC to install or run. To use a car analogy, an originally good car, in order to add certain features, is sent to a modification shop. The shop people can certainly implement this feature, but this doesn’t prevent them from installing some extra things on the car or replacing critical parts. After multiple modifications, the car gradually breaks down.

Second, apt-get manages both user software and system components simultaneously. In my view, dependency management is a complex system problem. The chaotic dependency relationships between software packages, with each node in the relationship network frequently updating itself, it’s not difficult to conclude that the uncertainty here increases nearly exponentially with the number of packages. There’s also an example of this: occasionally seeing developers who use npm complaining about node_modules is particularly interesting.

Here I clearly distinguish between user software and system components. System components are few in number, change slowly and are stable, and are mostly depended upon - these characteristics perfectly fit package management. User software, on the other hand, is numerous and diverse, changes rapidly and can die at any time, depends on a large number of libraries - this completely steps on package management’s landmines. When we try to integrate these two types of packages together, system components being “blown up” by some user software is to be expected.

Secondly, it introduces sandboxing. There’s no need to say much about what problem this solves. In recent years, both Microsoft and Google have been tightening permissions for user software on their respective systems. Users in China are also slowly becoming aware of privacy and security-related concepts.

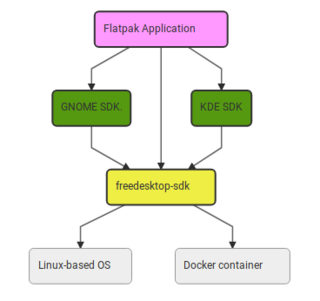

Then there’s unification. As everyone knows, Linux distributions are quite fragmented, even more fragmented than Android. I personally switched from arch to debian to opensuse back to debian and finally settled on fedora, and there are countless niche within niche distributions, while these distributions also have version fragmentation similar to Android. Then you also have to factor in desktop environment fragmentation: gnome/kde/cosmic/xfce/lxqt/.... This fragmentation brings a terrible user experience and has discouraged many developers.

Finally, from the developer’s perspective, there have always been two contradictory points.

First is the difference in system environment between developers and users, which is a fragmentation problem, but it has given Linux users a bad reputation, such as the common saying: the smallest number of users, but the most issues reported.

Second is with distributions, where the core contradiction lies in different requirements for dependency versions between distributions and developers. Distributions need a certain component to stay at the latest version or not update major versions, only updating security patches. Developers have one requirement: use the same dependency versions as the development environment.

How Does Flatpak Solve These

Runtime

- The runtime encompasses most common base libraries, such as glibc, libstdc++, libcurl, xorg suite, wayland suite, etc.

- Version numbers like 23.08/24.08, with one major update per year to introduce breaking changes, while regular maintenance ensures ABI compatibility.

- Libraries not in the runtime are bundled by the software itself, and libraries with the same name prioritize loading the bundled version. Similar to the Win/Android approach.

- Runtime is divided into Platform and SDK. Simply put, Platform is derived from SDK by removing header files, static libraries, compilation toolchains, etc.

Now that the basic situation is explained, some people may wonder why not directly use the host’s libraries, which would save more space.

Decoupling from the system - not depending on or assuming the host system’s libraries, so that even an ancient Debian oldstable can use the latest libraries and software. This also greatly solves the distribution fragmentation problem.

For developers, a determined runtime environment, the freedom to decide dependency library versions, allows more energy to be focused on developing software.

bubblewrap Isolation

An unprivileged sandbox implemented through Linux namespaces, details can be found on the project homepage.

It ensures that, with specified limited permissions, flatpak applications are isolated from the host environment.

Portal (xdp)

After isolating the host environment, we need a set of verified IPC interfaces to manage some sensitive host resources.

You can refer to Android permissions, though Android is based on binder, while xdp is based on dbus.

What’s quite interesting is that xdp has indirectly unified the chaotic desktop environment interfaces of Linux desktop. qt/gtk/electron/... have all now adapted to xdp.

Is Flatpak a Package Manager

Back to the article’s title, is Flatpak a package management tool? I don’t think so.

Our definition of package management is generally limited to software within Linux distributions that satisfies certain functions. Flatpak has many similarities with these software, but the approach is completely different. Most importantly, Flatpak cannot replace traditional package management; it’s more of a supplement, returning package management to the role of “managing system software packages”. Flatpak packages have very coarse granularity and unusually shallow dependency relationships, unable to build/operate fine components in distributions. For example, freedesktop sdk itself is not built through Flatpak but through BuildStream.

However, this is actually an open question, and readers can judge for themselves.

Or look at it from another angle, for example, is Android’s package installer a package manager?

Flatpak Tips and Technical Details

Runtime

/app

Let’s go into the runtime and take a specific look

$ flatpak run --command=bash org.freedesktop.Sdk//24.08

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ ls /

app bin dev etc lib lib64 proc run sbin sys tmp usr var

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ cat /etc/ld.so.conf

include /run/flatpak/ld.so.conf.d/app-*.conf

include /app/etc/ld.so.conf

/app/lib

include /run/flatpak/ld.so.conf.d/runtime-*.conf

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ ldd /usr/bin/ls

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007f4737637000)

libselinux.so.1 => /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libselinux.so.1 (0x00007f47375bd000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f47373be000)

libpcre2-8.so.0 => /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpcre2-8.so.0 (0x00007f473731d000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f4737639000)

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ echo $PATH

/app/bin:/usr/bin

You can see that this is actually equivalent to a minimal distribution following FHS.

/appAs the Prefix for each software, during compilation and packaging, only this directory is writable./app/libWhere software places bundled libraries/app/binIn the container’s PATH environment variable by default, the software’s startup program needs to be installed/linked here

host share

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ echo $XDG_DATA_DIRS

/app/share:/usr/share:/usr/share/runtime/share:/run/host/user-share:/run/host/share

[📦 org.freedesktop.Sdk ~]$ cat /etc/fonts/conf.d/50-flatpak.conf

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE fontconfig SYSTEM "fonts.dtd">

<fontconfig>

<!-- This has to be first so it is written while building the runtime -->

<cachedir>/usr/cache/fontconfig</cachedir>

<dir>/app/share/fonts</dir>

<!-- Then this so it is written when building the app -->

<cachedir>/app/cache/fontconfig</cachedir>

<include ignore_missing="yes">/app/etc/fonts/local.conf</include>

<dir>/run/host/fonts</dir>

<dir>/run/host/local-fonts</dir>

<dir>/run/host/user-fonts</dir>

<!-- This is duplicated from the general config because we want to write there

before the /run dirs, in case they are ever writable, like e.g with old

versions of flatpak. -->

<cachedir prefix="xdg">fontconfig</cachedir>

<cachedir>/run/host/fonts-cache</cachedir>

<cachedir>/run/host/user-fonts-cache</cachedir>

<include>/run/host/font-dirs.xml</include>

</fontconfig>

/run/host/share/iconsCorresponds to/usr/share/icons/run/host/user-share/iconsCorresponds to${XDG_DATA_HOME}/icons/run/host/fontsCorresponds to/usr/share/fonts/run/host/user-fontsCorresponds to${XDG_DATA_HOME}/fonts

Global Permissions

Flatpak can preset unified permissions for all applications.

This is quite useful, for example, I have a folder that no application should see, even with host permission.

$ flatpak override --user --filesystem='xdg-config/fontconfig:ro'

$ cat ~/.local/share/flatpak/overrides/global

[Context]

filesystems=xdg-config/gtk-3.0:ro;!xdg-run/keyring;/nix:ro;xdg-config/fontconfig:ro;

[Session Bus Policy]

com.canonical.AppMenu.Registrar=talk

[Environment]

MOZ_ENABLE_WAYLAND=1

Priority

The application’s own permission configuration has first priority, followed by global permissions.

However, filesystem permissions are a bit different, as they have their own priority. For example, host/home has lower priority than general paths. Roughly speaking, filesystem’s own priority is satisfied first before considering others.

system-wide and per-user

Similar to Windows’ install for all users vs install just for me.

Note that these two are completely independent, and if both are used, two copies of runtime are needed.

I recommend using per-user, but if it’s a shared home computer, system-wide is recommended.

system-wide

Installation location: /var/lib/flatpak/

Requires permissions to execute commands, distributions basically all have polkit rule installed, of course you can also use sudo

per-user

Installation location: $HOME/.local/share/flatpak/

Requires using the --user flag, added after the command